The case and the timeline

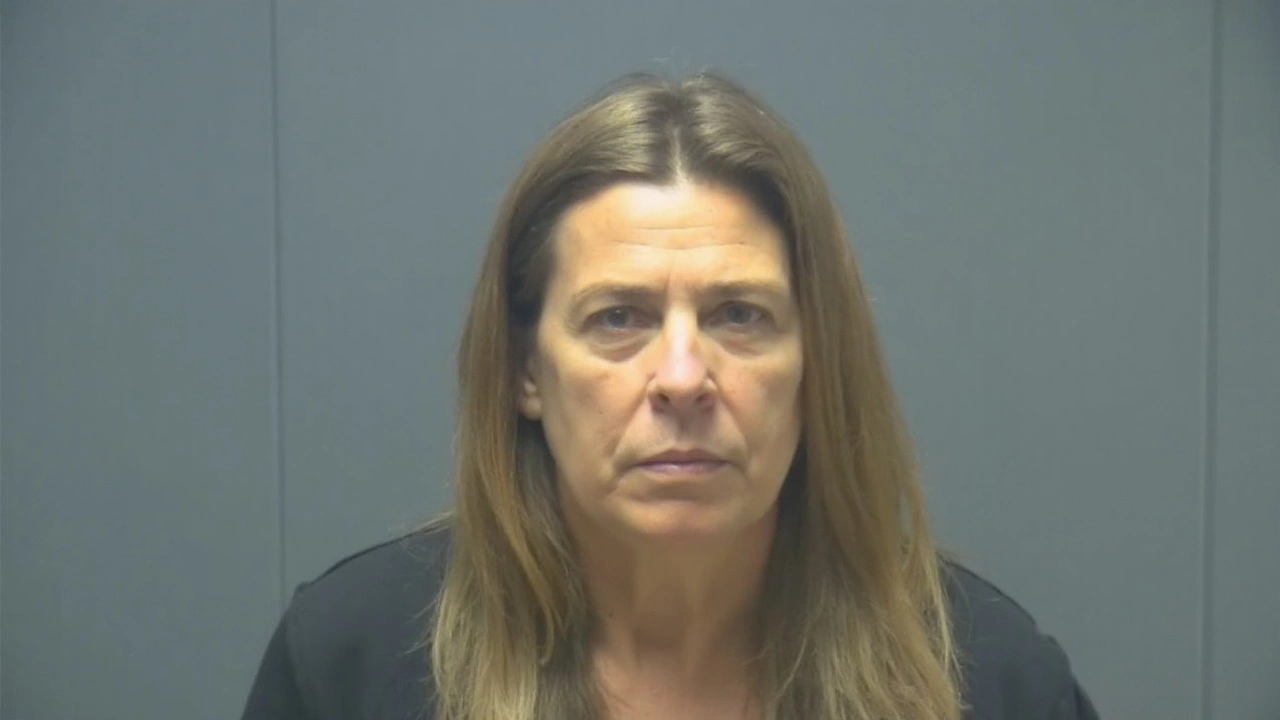

In Mount Pleasant, Michigan, a mother became the anonymous tormentor of her own child. Police say 42-year-old Kendra Gail Licari ran a months-long online harassment campaign that targeted her teenage daughter, Lauryn, and Lauryn’s boyfriend, Owen. Licari worked as a girls’ high school basketball coach at the same school her daughter attended, a detail that shocked the community once the investigation pointed to her.

The harassment started in September 2021 and ran through February 2022. The teens received up to a dozen messages a day across texts and social media—taunts, threats, pressure to break up, and, at times, messages urging Lauryn to kill herself. The posts mimicked the tone of a peer using teenage slang. One tell stood out: the sender called Lauryn “Lo,” a nickname typically used by close friends and family. That made the abuse feel personal long before anyone knew who was behind it.

Investigators say the messages appeared to come from another student who claimed to be interested in Owen. To hide her tracks, Licari used virtual private networks to mask her location and cycled through fake accounts. She also tried to steer suspicion toward a different student, according to authorities, a move that kicked the case into a higher gear as digital forensics specialists pulled logs, timestamps, and account data.

As police closed in, Licari told them she had gotten caught up in a fake-message scheme—an explanation that did little to slow the case. The scope of the deception, the volume of messages, and the effort to frame another student eventually led local investigators to bring in the FBI for technical support.

Licari was charged with two counts of stalking a minor, two counts of using a computer to commit a crime, and one count of obstruction of justice. She was arraigned on December 12 and released on a $5,000 bond. The top count carried up to 10 years in prison. In 2023, a judge sentenced her to at least 19 months behind bars for the cyberbullying scheme. The case later became the subject of a Netflix documentary, “Unknown Number: The High School Catfish,” which helped push the story into the national conversation about online abuse.

How investigators cracked it and why it matters

Cases like this don’t break from a single clue. Detectives typically build them piece by piece: login patterns, device fingerprints, recovery emails, and the timing of messages. VPNs can hide an IP address, but they don’t erase other signals. Platforms keep metadata, and people reuse habits—phrases, punctuation, sleep schedules—that tie accounts together. That’s the kind of pattern work that often draws in federal help when local departments hit the limits of their tools.

This wasn’t just trolling. It was sustained psychological pressure aimed at two teenagers who believed a classmate was out to get them. Research backs up the harm. The CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey has consistently found that around one in seven U.S. high school students report being electronically bullied in the past year. A 2022 Pew survey reported nearly half of U.S. teens have faced at least one type of online harassment. The risks grow when the abuser knows intimate details of a victim’s life, which is exactly what made this case so disturbing.

If you’re wondering how something like this can drag on for months, consider the mix of secrecy and plausibility. The messages looked like they came from a peer. The language fit. The nickname “Lo” made it feel like an inside circle. And the use of VPNs made early technical checks a dead end. Only after the volume and intensity ramped up—and the attempt to frame another student surfaced—did the case get the forensics time it needed.

Law enforcement charged Licari under Michigan’s anti-stalking statutes and computer-crime laws. The obstruction count came from the alleged effort to pin the harassment on someone else. Those charges track with how these cases are usually built: a mix of conduct (stalking) and method (using a computer to commit a crime). The sentence—at least 19 months—reflects a judge’s view that the sustained nature of the abuse and the breach of trust outweigh claims that this was just a lapse in judgment.

So where does this leave schools and families? Beyond the shock, it’s a reminder that abuse can come from unexpected places. It also shows why documentation matters. Saving messages, noting times, and reporting early give investigators a head start when they have to pierce layers of digital cover.

- Keep a record: screenshots, dates, times, and platforms used.

- Report patterns, not just single posts—volume and frequency matter.

- Lock down recovery emails and phone numbers tied to accounts.

- If threats escalate or identity framing appears, contact police and your school right away.

The Netflix documentary turned this local case into a national cautionary tale, but the core lesson isn’t cinematic. It’s routine and uncomfortable: people who know us best can misuse that access. That’s why schools and parents now treat severe online harassment like any other safety threat—triage first, preserve evidence, and escalate quickly when messages pile up.

And the term that’s become shorthand for this type of deception—catfishing—doesn’t capture the full damage when the target is a child and the abuser is a parent. This story traveled because it inverted the roles we trust most. The legal outcome is one part of the response. The other part is rebuilding a sense of safety for the teenagers who spent months thinking a classmate wanted to hurt them, only to learn the cruelty came from home.